On my writing table this morning sits The World Treasury of Modern Religious Thought, edited by the late Jaroslav Pelikan. It came in a box of six or eight books I received thirty years ago, as an undergraduate, for little more than returning a postage-paid card to the Book of the Month Club, a transaction I so naively mistrusted. The book has a cover to distress anyone with taste: sunshine exploding through backlit clouds. Not so unlike our sunsets in Los Angeles, I suppose, though drained of anything roseate. Heaven breaking into view? A New Day dawning? More like a magnesium flare in a battlefield fog. But we’re approaching an image I could have gotten behind.

The book concludes with an excerpt from Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s 1970 Nobel Lecture, under the title “Beauty Will Save the World.” Like that bewildered savage who has picked up a strange object…, it begins, and proceeds to an analogy in which we are that savage and art is that object. The object is “intricate in its convolutions,” alternately glows and flashes with a strange light, and the savage “keeps turning it over and over in his hands in an effort to find some way of putting it to use, seeking some humble function for it, which is within his limited grasp, never conceiving of a higher purpose….” Inquisitive savages, as any parent will attest, can be hard on strange objects. But art, Solzhenitsyn assures us, can take it. In every clumsy use to which it is put, “it sheds on us a portion of its secret inner light.”

What puzzles me about this piece in my Treasury is its virgin margins, the absence of even a single underlined phrase. My entire adult life, this notion, in these words—beauty will save the world—has colored my most personal thoughts, and I’ve never forgotten where I first met with it and fell under its influence. On the other hand, turning to, say, an excerpt from Weil’s Waiting for God, I find its margin arabesqued, entire paragraphs underlined, in the hand of an ardent young Philosophy major. I have no memory of reading it.

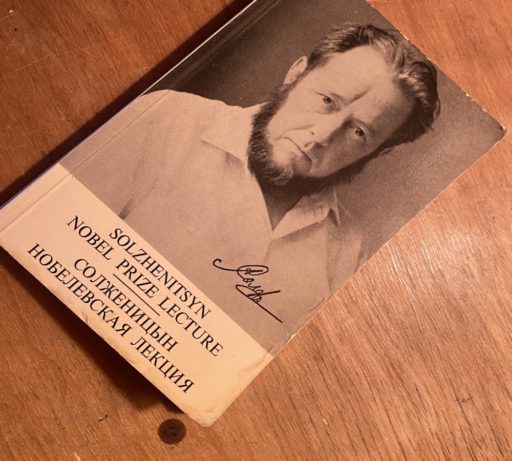

Several years ago, stretching a lunch break from my office in a courthouse downtown, I happened upon the full text of Solzhenitsyn’s lecture in a favorite used-book shop down the street. A beat-up little booklet, Russian and English on facing pages, our burly author on the front, staring into the camera with what I’m willing to suppose is inimitable frankness. This copy I have penciled up in the fashion of my middle age, quick ticks and para symbols mostly. And often it lies within reach of whatever desk or table I am sitting down to each morning to work on a story, a poem, the memoir-ish argument I may well be losing with Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. “Of course,” he once let drop, “the law is not the place for the artist or the poet.” Against the persistent resonance of this remark, my little booklet has become something of a talisman.

As seems right with a talisman, I’ve balked at querying its power. I reread my booklet from time to time, but usually it’s enough simply to recall its physical existence. Its chipped red back, blunted corners, notepad’s weight—from these I draw some inarticulate reassurance. When on occasion, for reasons equally inarticulate, I’ve felt I should maybe try to account, just a bit, to myself, for my talisman’s power, the urge never seems to survive beyond my observing the almost physical sense I have, turning this booklet’s pages, that there is nothing inherently discordant in the life I have stumbled, drifted, chosen my way into—somewhere, if only in the mind of the wise, art and law are of a piece.

If it was sage to leave well enough alone, I slipped up last month adding Solzhenitsyn’s lecture to the syllabus of a Law and Literature course I’m teaching at a local law school. Surely now I needed some intelligible comment on it, some ready defense. At least one faculty member, after all, had pushed back against the course on grounds of, well, frivolity. Fortunately, the dean who hired me had a delightfully simple view: the course would make students better people, and better people would make better lawyers. It carried the day, who am I to quibble? But for the Solzhenitsyn piece I was on my own. In the end I muttered to myself something about it offering an aesthetic that relates literature to morality, politics, and even the global order without succumbing to the instrumentalism of the savage. Eh. Close enough for adjunct work.

But did I say I added the piece to the syllabus? Friend, I began the course with it. We introduced ourselves, shared reasons for being here, covered some ground rules. Then I said, as distracted as I sounded, “Allll righty…so…” I had not anticipated just how much respect, how much admiration, I would feel for this small, diverse, self-selected group. They had read War and Peace “twice, but in Spanish,” their families had fled Armenia to escape Stalin, they were raising children, running businesses, staffing offices, nearly every one of them holding down a full-time day job while attending law school in the evenings, on the weekends. Had I really required these serious, ass-busting, tuition-remitting people to read an essay suggesting—I could barely bring myself to mouth it—beauty will save the world? What was I going to say for this in the face of their withering skepticism, their yawn of silence?

What was I going to do if they crushed my talisman?

We’ll never know. This in-earnest group talked on top of one another in their enthusiasm for the piece, their quoting, questioning, glossing, probing. They didn’t need me to defend squat. They needed me to direct traffic and otherwise, largely, keep out of the way. They did also need me to close the discussion finally, which I did with an apology for letting class run long by a quarter of an hour. The one thing I said that morning that was not entirely heartfelt.

I keep returning to a passage that, by the end, we found ourselves focused on. Not that I have to know, but it must, I suspect, lie rather near the heart of my talisman’s power.

Can it be that the old trinity—Truth, Goodness and Beauty—is something more than a well-wrn, forlorn cliché…? The wise men of old used to say that the crowns of these three trees merge, while the branches of the Truth tree and the Goodness tree, being too obvious and too straight, are crushed, lopped off and not allowed to grow. But if this is the case, maybe the fantastic, unpredictable, unexpected branches of the Beauty tree could fight their way through the rest and right up to the same place, and thus achieve the task of all three?

Here, it seems, is an image I can get behind.

Chad Holley is a 2022 Lincoln City Fellow in the arts. He lives in Los Angeles, where he works as a judicial attorney with the California Court of Appeal.