The Finest Mystery

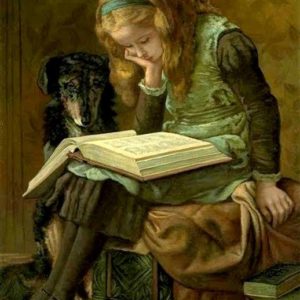

My mother read mysteries by American authors, but I have never been interested in mysteries set elsewhere than in England. The best of all such mysteries, in my opinion, and perhaps the one that best justifies my feeling for the genre, is the one that I have just re-read, Sayers’s finest work, The Nine Tailors.