I bow down to you, O Warty Pig!

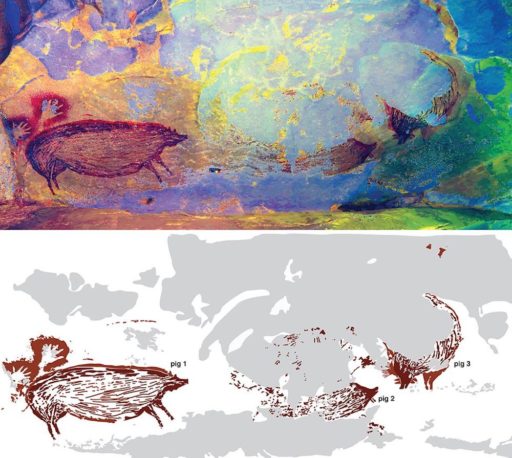

There’s a bit of backstory here. The warty pig in question is a depiction on the inside of a cave in Indonesia. The painting was discovered last year. It was painted, the carbon daters say, about 45,000 years ago. That’s more than 10,000 years older than the famous paintings at the Chauvet Cave in France. Warty pig is, for now at least, the oldest work of representational art, by far, that exists anywhere in the world. 45,000 years. A long time. Also not a long time, geologically speaking. Just a blip. For us, though, for us, a very long time.

Anyway, the painter of warty pig, whoever this person was, seems to have been working on a domestic scene going on between at least three warty pigs. And what might have been the important business amongst the warty pigs on the island of Sulawesi during the forty-fifth-thousand-and-first century BCE? Well, the Sulawesi warty pig lives on the island to this very day. So, we have a pretty good sense of what the pig would have been doing 45,000 years ago. It would have been wandering around in the mornings and early evenings, rooting around in the underbrush looking for goodies to eat. It would have been working out whatever things needed to be worked out in the small social groups in which the pigs tend to live. Maybe that’s what the cave painting is showing us, an impromptu meeting of warty pigs 45,000 years ago. Unfortunately, the images of the other pigs have been lost to us but for a few scraps of color and shape. We’ll never know exactly what was the greater context for this image.

But here are a few things that I love about this fragment that has passed down to us from the deepest recesses of the past. This warty pig is pretty ugly. Yes, I understand, what do we mean by ugly, who gets to judge? Perhaps to other warty pigs this was an especially stunning pig, one of the top pigs of the era. Possible. And why do we consider one type of animal more attractive, more pleasing than another? And who is ‘we’? Perhaps the people of Sulawesi, then and now, are more inclined to appreciate the specific physiognomy of the warty pig. But that’s the point. The point is that now we all must have eyes for this pig, the warty pig of Sulawesi. This warty pig is the ur-image, right now. This pig is the vision of animal life that stands at a point of origin. It is older and more primary than any other existing image. We must reckon with Warty Pig.

The warty pig, as depicted by our ancient artist, is mostly belly and that belly is covered in thick, spiny hair. The warty pig has a tiny head upon which the artist seems to have spent relatively little time. The legs are chicken-like, spindly to a comical degree. You could describe the animal, not unfairly, as a giant lump of hair perched on twigs. Still, there is an interesting streamlined quality to the fur of the pig. It’s like a lump of hair that has been combed over and over again in the same haunchy direction for many years.

And then there’s one more startling feature to this warty pig painting. The person or persons who painted it also made an outline of two hands in the paint, just above and to the rear of the pig. A right hand and a left hand. Do these hands belong to the same person or two different people? The way the hands are positioned behind the pig creates something close to a ‘Voila!’ moment, a big reveal. Here it is, the hands say. Behold! Feast your eyes! Warty Pig!

It is interesting, is it not, that the painter(s) of the pig include human hands but not human bodies or faces. It is as if the painting is saying that the being of the being that is human is the being of hands and that the being of hands is the task of revealing, of showing, of looking-at, of having-concern-for and being-interested-in other creatures. These subtle and funny and even creepy, bony, long-fingered human hands. These hands are a tool for paying close attention to all the other beings and, in this case, to one sort of being, to piggy-being. These hands are put in the service of warty pig, which, for its part, seems to be engaged mostly in the project of being an impressive, ponderous and even somewhat distended belly. Human-being is handy-being and piggy-being is belly-being. Or something like that.

The hands that painted warty pig and that also painted themselves, these hands are not judging hands. They are not the hands of the critic. They are the hands of the artist. By artist I mean one who takes experience and then pulls it closer in. It is going to sound absurd, what I am about to say. It is going to sound hopelessly dewy-eyed to some people when I claim that the hands behind warty pig, the hands saying Behold! Warty Pig! that these hands are in love with warty pig. But there it is. Will I dare to say that these hands are in some kind of intimate embrace with warty pig? And that these hands are also the hands of a kind of implied respect and distance as well. They don’t violate the necessary space. These are the hands that acknowledge that warty pig is warty pig. The hands have just the right approach, close but not too close. Identity and difference. Connection and separation at once. Love, which could never happen at all were there not also originary separation. A kind of pain and longing in these hands. A wanting and a hovering just at the edge of that wanting. An acknowledgment that desire exists precisely because of the unbridgeable gaps within and between all beings, all Being.

So these hands spell out a kind of ode: O Warty Pig, you are so much exactly just what you are. That is all, really, that we need to know. That warty pig is warty pig, this is both consolation and sweet melancholic despair all at once. Warty Pig is life. Warty Pig is hope.

I bow down to you, O Warty Pig!

Morgan Meis has a PhD in Philosophy and is a founding member of Flux Factory, an arts collective in New York. He has written for n+1, The Believer, Harper’s Magazine, The Virginia Quarterly Review and is a contributor at The New Yorker. He won the Whiting Award for non-fiction in 2013. Morgan is also an editor at 3 Quarks Daily, and a winner of a Creative Capital | Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grant. A book of Morgan’s selected essays can be found here. His new book from Slant is The Drunken Silenus. He can be reached at morganmeis@gmail.com.