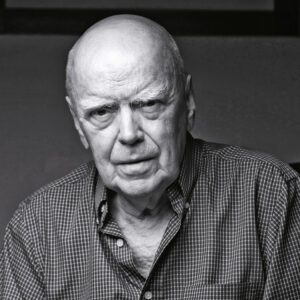

We recently interviewed Thom Satterlee, author of God’s Liar: A Novel, just published by Slant.

Tell us about your beginnings as a writer. When did you first know that you wanted to be a writer?

Midway through my junior year of high school, I decided that my boyhood dream of becoming a professional soccer player wasn’t going to work out—I wasn’t good enough, basically—and I faced, not to be too melodramatic, a kind of void. Up until then soccer had been my identity. What was it going to be now? I had to be something, right? Around that time a friend came to me with a problem. He’d asked me to do his English assignment for him, which was to write a sonnet, and I’d written one happily and he’d passed it off as his own without the teacher ever suspecting otherwise. In fact, the teacher really liked “his” sonnet and wanted to submit it to a student writing contest. And this was the problem. What if the poem won the contest? What would we do about the prize money?

Did it win?

No. Or if it did my friend pocketed all the money. He never said anything more to me about it. But I’d gotten what, at that time, I needed: a new aim in life. I’d always enjoyed writing, and my teachers had praised me, but this time writing filled a void. Instead of becoming a professional soccer player, I’d become a writer. And I’m the sort of person (was then, am now) who likes to have a goal to work toward. Mastering the art of writing is a lifelong pursuit. Within it are lots of small goals to work towards. If I had made it in soccer, my playing days would have ended decades ago. I suppose then I would have found something else to do with myself; still, I’m glad I made the purpose-in-life adjustment relatively early and, honestly, I can’t imagine anything taking writing’s place.

You also translate Danish poetry and fiction. Do you get the same enjoyment from translation as you do from your own original writing? And how do you manage the work-flow between the two?

Translation is a creative art, definitely. And the work is, I find, pleasurable because I’m working with language, material that I enjoy. But there is one big difference between the two. When I’m writing something original, I occasionally pause, look over the top of my computer screen, searching for the right word until I remember or think of it, then go on working. Well, with translation, at least for me as someone who’s not perfectly bilingual, this hunting for a word happens much more frequently and often involves searching through two or three different dictionaries, and sometimes asking a fellow Danish translator for help. I guess I would have to say that my creative flow is interrupted more when translating. But once I’ve understood what something means in Danish, it’s fun to try to match it with equally expressive English.

In terms of work-flow, I move between translation and original work without any specific plan, really. I almost always have an original project that I’m working on; but my process is slow, and finishing a book usually takes several years. If, in the meantime, I’m asked to translate a specific work, I just interrupt what I’m writing or researching and concentrate on translating for a while. I enjoy both art forms. I’m lucky to have the time to devote to both.

You say a book usually takes you several years to write. It probably varies from book to book, but do you find there is some average length of time it takes?

In The Writing Life, Annie Dillard says a writer should expect to work at least five years full-time in order to produce a book that might have a shot at lasting. She notes the outliers, works such as Faulkner’s Light in August and Rilke’s Duino Elegies, but says those are freaks of nature, really. I’ve kept her five-year rule in my mind, and it’s been a comfort whenever it seemed like a book was taking a very long time to finish. The last one, from when I started it to when it was finally published, took almost seven years.

That would be your latest novel, God’s Liar. Can you tell us how it got its curious title?

“God’s Liar” refers to the narrator, Rev. Wesson, who tells a lot of lies over the course of the novel. At one point, toward the end of the book, he tallies up his many lies and calls himself “God’s Liar.” It’s unclear what he means by that title. Does he think of himself as having some sort of divine license to lie? Is he lying on God’s behalf, or with God’s approval? I’m not sure he knows why he calls himself “God’s Liar.”

Of course, as a writer of fiction I’m a liar, too. I tell lies with the aim of creating a story that may possibly resonate with readers and may even reveal truths about being human. However, I would never call myself “God’s Liar.” Doing so just seems too presumptuous, too grandiose for my tastes. I prefer to think of myself as the person who wrote God’s Liarrather than actually being “God’s Liar,” whatever that might mean.

John Milton figures quite prominently in this novel. Why did you choose to include him?

The whole time I was working on this novel, I thought of it as being about John Milton. He was central to everything from the start, really. My computer folder where I kept all my drafts and notes was called “Milton Novel.” His name appeared in several “working” titles: ‘Milton’s Cottage,’ ‘Milton’s Scribe,’ ‘A Companion to Milton.’ But novels are known to shape-shift, and this one was no exception. I wasn’t satisfied with my attempts to write the novel from Milton’s point of view. I tried it first-person John Milton, and I tried it third-person limited John Milton, but I wasn’t happy either way. Two or three years into the work Theodore Wesson came forward and offered to tell the story. He had an interesting twist, and I enjoyed hearing his voice, so he got the job. But when you say that John Milton figures prominently in the novel—and he does; he is central—I have to point out that he was intended to figure even more prominently.

Now, in terms of why John Milton… that’s a hard question for me to answer. I could say that he’s a fascinating character and lived during interesting times, but the same could be said of many other historical figures. I’m tempted to say it was chance. In late 2013, I had finished one writing project and was looking for something new. I happened to be re-reading Paradise Lost, I can’t remember why, but there’s probably no bad reason for re-reading Paradise Lost; anyway, it struck me more powerfully than before that because he was blind Milton had had to dictate this epic poem to scribes. I got wondering about what that looked like. What would it have been like to sit across from John Milton as he recited the newest lines for his poem?

Are any of the other characters in this novel based on historical persons?

Yes, in fact, the young man who comes to visit Rev. Wesson and stays for a day of storytelling is based on one of John Milton’s earliest biographers, John Toland. The quotes that begin each chapter come directly from his Milton biography. Milton’s wife, Elizabeth, is of course also a historical person; but we know very little about her, so I have felt free to invent her character based on those few facts. Isaac Pennington is yet another historical character who makes his way into the novel.

It must have been a challenge writing about seventeenth-century England. How did you go about researching for this novel?

Well, I started by reading all of Milton’s poetry and a lot of his prose; then a recent critical biography, followed by several contemporary accounts of his life. Then I moved on to books that helped me understand the historical moment that Milton lived in—so much that was new to me! I also took a trip to Chalfont St. Giles, and visited the cottage where John Milton lived during the summer of 1665. The cottage still stands; it’s a museum now, with a garden that contains many of the plants and flowers Milton mentions in his works. For about half an hour I was allowed to sit alone in the very room where Milton had his study—the spot where he may, quite possibly, have dictated the final lines of Paradise Lost.

Have you written other works based on historical periods and/or people?

I have. My poetry collection, Burning Wyclif, is about the fourteenth century theologian John Wyclif; and my first novel, The Stages, is about the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard—although the latter is set much nearer to today—in 2013, during the bicentenary celebration of Kierkegaard’s birth.

Are you working on anything new?

I think I may have another novel in me, possibly something more autobiographical than the previous ones. At this stage, though, I’m just preparing to write, which I do by following my curiosity where it leads me—reading books and jotting down notes and ideas—and then, at some point, I expect I won’t be able to help myself: I’ll write something new. It’s what I’ve done since I was a teenager.