It’s eight-thirty in the morning on a weekday, I’m running late for work, and I am stuck in traffic on Route 50 heading west into Washington, DC, when my mind is sliced by a line from a poem.

The line actually angles into my head—not unlike the glare of the morning sun that is slashing through the car: The expense of spirit in a waste of shame—.

Where did that come from? And why, today of all days, did that particular line assert itself out of the black box of my brain?

With the advent of that line, though, I was off—as though I were trying to skip from one stone to the next forward on a path:

The expense of spirit in a waste of shame Is lust in action and till action lust…

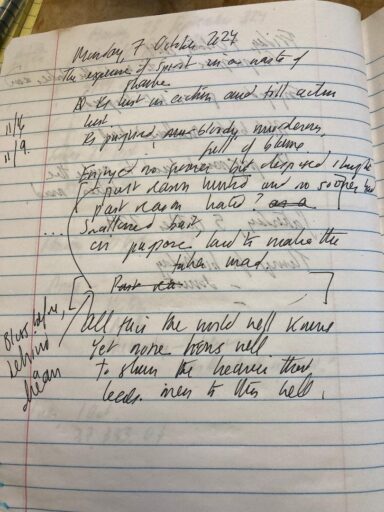

And till action lust is what? I had to get to the office downtown and furtively pull out my trusty notebook to start working out the rest with pen on paper, to see if I still remembered it:

The expense of spirit in a waste of shame Is lust in action and till action lust Is purjured, murderous, bloody, full of blame…

Then something something something, though the windup for the dramatic closing lines was right there waiting:

All this the world well knows, yet none knows well To shun the heaven that leads men to this hell.

But I could not for the life of me—at that moment—recall what came in between.

The poem is, of course, Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129. And the only reason I even knew this much of it was because one of my professors in graduate school, the poet Cynthia Macdonald, insisted on it.

Macdonald was the magisterial founder, along with novelist Donald Barthelme, of the MFA program at the University of Houston. She was a poet and psychoanalyst who’d also been married to an oil company executive and who carried herself with a different air of authority than the kind of suspicious defensiveness that most writers—even famous and rich ones—had. She wore expensive Ferragamo Varo heels with the brass-and-grosgrain bows.

On the first day of her poetic “forms” class that we were required to take, she declared that each of us would be required to pick one of Shakespeare’s sonnets and memorize it, to widespread eye-rolling and groans around the seminar table.

I picked Sonnet 129 mostly because, at the time, the sonnet’s edgy tone about the drive to tamp down the earthly passions–—something I was personally dealing with at the time!-—cohered to my own struggles. I scrawled the poem in cursive on notebook paper over and over, trying to memorize it, and in memorizing it, it became a part of me—a part of my body, really—in a way that a poem that I might have initially chosen as being personally significant just to me ultimately cast me as the conductor of its own purposes. I did not matter—it was the poem that did.

On the day that we were required to recall it from memory, the words came out finely and exactly crafted on the page.

Hence, its mystical reappearance on Route 50 on a weekday morning. The subject matter still had its relevance, thirty years onward into my own adult life, but it was the form of the sonnet that had impressed its residue onto me. It was the form that made the boundary. And the boundary still had purchase in my mind—even if I could not, at the moment, remember the words.

Over the following week, I ransacked my mind, evaluating the sonnet again day by day, for what order the words came in, what things I was missing.

The expense of spirit in a waste of shame Is lust in action and till action lust Is purjured, murderous, bloody, full of blame Enjoyed no sooner but despised straight .…

Where did “swallowed bait” go, I wondered. But then it fell in line:

Past reason hunted, and no sooner had Past reason hated, as a swallowed bait, On purpose laid to make the taker mad.

I was getting close, but still there were holes, and they were driving me crazy. I knew that after “make the taker mad,” there was something about

…Before a joy proposed; behind a dream

before the rousing finish. And I was determined not to look it up: if all the other lines had been mystically “there” this whole time, as if frozen in amber (or perhaps, for this Gen Xer, Jello), then why could I not yank up these last couple?

Finally, though, I just could not remember, broke down, and learned that there were actually three lines I’d not managed to recall:

…Mad in pursuit and in possession so, Had, having, and in quest to have, extreme; A bliss in proof and proved, a very woe;

It was the final stone in the construction, and the building came together. I’m determined now to firm the foundation, and make sure that I can remember it all.

Making that vow, I thought about a hot June day two summers ago, where on the gray-painted porch of his house in my Mississippi hometown, I listened to my family’s dear friend Sam Olden, then 102, crouch forward in his wheelchair and with eyes that saw both the seen and unseen, quoted Tennyson’s “Ulysses” from memory. And how wonderful to see those words, his joy–his body at once with the words and the universe. He would not live two more months, but I still remember the reverberations of his recitation.

Caroline Langston was a regular contributor to Image’s Good Letters blog, and is writing a memoir about the U.S. cultural divide. She has contributed to Sojourners’ God’s Politics blog, and aired several commentaries on NPR’s All Things Considered, in addition to writing book reviews for Image, Books and Culture, and other outlets. She is a native of Yazoo City, Mississippi, and a convert to the Eastern Orthodox Church. She lives outside Washington, D.C., with her husband and two children.