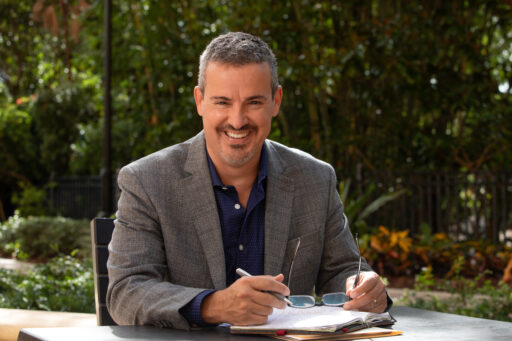

We recently spoke with author Tony Woodlief about his new Slant book, We Shall Not All Sleep

What inspired you to write this novel?

One day for reasons unknown I was struck with this image of a boy riding with his father along a back country road. When I put myself in that boy’s shoes, I couldn’t help but see from the perspective of my own boyhood, which put them in North Carolina, and made the boy’s father a Vietnam combat veteran—someone big, powerful, and dangerous, as my stepfather was (or at least that’s how I saw him at the time). Along with this image came a sense that it’s going to be the last day of this boy’s innocence, that they’re headed for a terrible accident. I envisioned them barreling toward a town. They aren’t just heading into a tragedy, because to a little boy and his family in that town, they are the tragedy. The more I thought about the three of them—the boy, his father, and the boy whose life is about to end—the more I began to envision their families, friends, enemies, until even the town had a kind of personality, as well as the lands around it. At first I figured this would all work itself out in a short story, but I slowly realized that no, this boy and his father need to have a reckoning. And the dead boy has a role to play in that.

Talk about your idea of haunting.

When you lose someone with whom you are intertwined, the string of your life doesn’t go slack. We call the kinks in a flyfishing line “memory.” What a hard, lovely, true metaphor. Our lives still bear the shapes of our departed people, is what I’m saying. Only now we’re fitted not to their presence, but to their absence. The Portuguese call this haunting saudade: the presence of absence.

Do you believe in revenants?

No. I believe people die whether or not they deserve to, and they don’t come back to us. Instead we go to them—one day, after waiting far longer than we think our hearts can bear.

Why did you choose We Shall Not All Sleep for the title?

The most immediate reason is because of the revenants who appear to Daniel and his father, bearing with them the history of this community and its people. Daniel learns that the dead don’t just lie down and sleep. And often neither do the living, at least not well. Beyond that, readers who recognize the allusion to 1 Corinthians 15 (“We shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed . . . and the dead will be raised incorruptible”) might glean a clue about what’s in store for revenants and living alike. Ultimately this is a story about transformations—both the kinds that are imposed on all of us against our will, and the kinds many of us long for.

Revenants are not only prominent in the eyes of your characters, sometimes they speak directly to the reader. What inspired that choice?

Perhaps to compensate for his blindness toward the mysterious realms into which his father Ray gazes, Daniel delves into histories—of his family, their town, the people who shaped it. But how to see widely and deeply enough into the past to truly comprehend even a portion of its grace and horror? All around us are shoddy histories that impart shallow judgmentalism rather than a rich understanding that is only ever—since we are dealing with complicated human creatures—complicated and hard-won. Allowing the dead to speak is a way to offer the reader a fuller view of his community than Daniel can sometimes manage. My hope is that by the end you don’t hate even the most hateful of characters, nor do you love your favorites too sweetly.

There are many mystical elements in this novel, especially from Native American culture. How did you come by these influences?

Not honestly, if that’s what you’re getting at. When I was a young man, my father informed me that his mother, who had been absent nearly all his life, possessed some impressive apportionment of Cherokee blood. I learned mighty quick that this doesn’t impress; everybody’s Cherokee nowadays. It doesn’t matter what’s in my blood regardless, because I was raised like every other poor white boy in my neck of the woods. Everything I think I’ve learned about the Cherokee, the Creek, and other small and neglected southeastern American tribes, as well as the bits of African slave culture that filter into this novel, came from books, diaries, and published interviews. And please keep in mind that these claims are coming not from me as some self-declared amateur historian, but from flawed and sometimes ill-informed characters, with the purpose of advancing the narrative, not getting all the historical facts right. If you want to learn more about these cultures (and I hope you do), please read actual sources. As for the mythological underpinnings, in particular the idea of the dreaded “room without walls,” I drew on Joseph Campbell. I’ve done my best to be faithful to all these accounts, especially to their mysteries, without presenting myself as speaking for or from them.

Is the fictional town of Hickory Shore, where much of your novel is based, drawn from your own hometown?

My attorney would like me to remind you that any resemblance the characters or events in my novel might bear to actual persons (living or dead), or events (past, present, or future), is purely coincidental. Besides, I probably grew up at least thirty miles from the place where I situate Hickory Shore—not that I have any particular place in mind, of course, other than a winding riverbank where people who are somewhat like the people from my childhood—but in no way like actual people, mind you—might have lived, had they lived, which they most certainly did not, this being a work of fiction.

What fathers in literature stick in your mind, and why?

Well there’s Atticus Finch, of course, who is a moral compass not just for his children but for his community, even if many of them don’t know how to use a compass. And there’s the saintly Jeremiah Land in Leif Enger’s Peace Like a River. I recognize that I’m giving myself impossible standards, but a man needs someone to look up to, and he damn sure can’t find anyone in the newspapers these days. Finally there’s the father in Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, whose little boy calls him Papa. My youngest children call me Papa. Oh, my heart, that last chapter broke me.

Fatherhood is prominent in this novel, and it’s also a topic about which you’ve written extensively in your essays and a memoir. Why?

I’m tempted to give you a high-minded statement about the decline of fatherhood and what that means for communities. I guess the real answer isn’t unique to me. It takes the form of a question faced by many men I know or have heard from over the years: How can I be the father my children need when nobody showed me how? Hard on the heels of this is a deeper, more painful question: Was I good enough for my father? Look past the revenants and knife fights and mystery-solving and love stories in We Shall Not All Sleep, and that’s what you’ll find: a boy trying to understand what he is in his father’s eyes. My heart will always be with that boy. In a way I am him, and I suspect a good many other sons and daughters are too.

Do you think your novel would make a good movie?

You’re damn straight it would. Somebody get a copy to Matthew McConaughey, and tell him I’ve already got the soundtrack put together on Spotify.

What writing projects are you working on at present?

I’m writing a novel about this widowed father, a former Ukrainian Olympic wrestler, who has trained his son and young daughter so well that they win wrestling tournaments all over the Midwest. For complicated reasons, he loves America (especially Ronald Reagan) but doesn’t trust any government (especially the Russian one). He works as a janitor in a small Iowa university so he can homeschool his children and hide in plain sight by living in the basement of the university library. The novel is narrated by his daughter. I think I write best when I use the voice of a child. Probably because it keeps me from getting too fancy.