I want to talk about seeing angels and about speaking with angels. I myself have not seen an angel. I have also not spoken with angels. I’m not even sure what an angel is. I’m not just saying that I doubt the existence of angels, I’m saying that the whole concept of an angel, even as a literary or biblical trope, is obscure to me. Nonetheless, I can’t stop thinking about angels.

That’s probably because I’ve been handling a lot of old books lately. There’s a long story behind that, a story I can’t get into in any detail right now. But I’m involved in a project with a good friend that involves the buying and selling of old books, books that harken from the early age of printing in the early 1500s into the late 1700s. We’re especially interested in books that are categorized broadly as esoteric, or occult, or arcane. This is the period in Western history where the seeking of knowledge and wisdom created fascinating overlaps between alchemy, demonology, neoplatonism, hermeticism, early ‘science’, mysticism, etc. Later Enlightenment polemics largely relegated this period of intellectual history to obscurity. So, it has become a largely forgotten and marginalized subject matter.

But it is out there still, embedded in the history and the just-below-the-surface you might even say ongoing unconscious inheritance of all the thoughts that we’ve been thinking and sharing and writing and repeating for centuries. These things don’t just go away. They go under, perhaps. They hide and they linger and they return, as the repressed always do.

Sometimes they come back in the form of angels. We’ve never stopped thinking about angels, in short. We can’t seem to stop thinking about angels, or dreaming about them, or referring to them. Everyone has heard of angels. But rarely does a person pause to consider what it is they’re really thinking about.

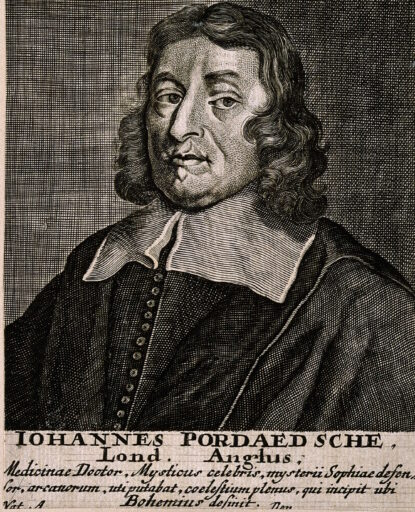

I was flipping through a 1715 German edition of John Pordage’s Divine and True Metaphysics that happens to be in my possession. John Pordage is a fascinating figure. You could tell stories, and then stories of those stories. He was brought up on heresy charges in the mid-seventeenth century (though acquitted). He got into trouble for basically practicing medicine without a license. He was always operating at the very outside edge of what he could get away with and what the English society of his day would let him get away with.

He was also accused of communing with spirits. This could have gotten him into a fair amount of trouble, since that’s a half step away from being accused of witchcraft, and being accused of witchcraft is, generally, not the situation in which you want to be in seventeenth century England. This was the era of famous and notorious witch hunters like Matthew Hopkins, who sent many a soul to the gallows.

Communing with spirits basically means that Pordage was talking to angels. He was talking to angels so much that someone else noticed and reported this behavior on down the line. Okay. So Pordage was an angel talker. But what does that mean, really? And where and how did John Pordage learn to talk to angels?

It seems that he picked this up from reading Jakob Böhme, the great German philosopher and mystic, the cobbler from Görlitz. And the fact is that no one is sure where Jakob Böhme learned to talk to angels, or really learned anything he learned, much of which seems to have emerged from his own very unique brain and consciousness and just the Jakob Böhmeness of Jakob Böhme. He was a strange and extraordinary fellow who seemed to emanate incredible mystical thoughts and visions with roughly the same ease with which he emanated shoes.

John Pordage had a great feel and intuitive sense of what Böhme was getting at and started to produce his own mystical writings and then he handed those down to Jane Leade, who is another of the more incredible mystics of the seventeenth century and who also communed with all sorts of angels and for whom the most important of all these angelic powers was an angel who was the personification of Wisdom itself, the ancient and biblical Sophia, who was and always shall be associated with the feminine. Sophia would come sometimes and just stand right in front of Jane and sometimes would be wearing a crown. Or perhaps we should just let Jane Leade herself describe it.

“Now after three days, sitting under a Tree, the same Figure in greater Glory did appear, with a Crown upon her Head, full of Majesty; saying, Behold me as thy Mother, and know thou art to enter into Covenant, to obey the New Creation-Laws, that shall be revealed unto thee.”

Very old-school biblical prophet kinds of talk and behavior here. But it is interesting also that what Sophia is going to reveal to Leade is “new creation laws.” That’s to say, the angel is herself wisdom and wisdom is a kind of way of doing things and when there are ways of doing things we can call these laws. Don’t think of “law” in the juridical sense so much. Think of it as a way. The way things are. Or the way that things can be.

What I’m trying to get at here is that for Leade and for Pordage and for Böhme when we speak of angels we speak of the way things are. The angels are a way for the way things are to speak of themselves. The angels are a means by which the actual functioning of the world in its deepest functioning, the functioning we don’t always have access to and that can therefore seem hidden and obscure, the angels are a way for this to suddenly shine forth and to make itself clear. The angels are that moment of realization. Ah, things are like this.

At least, that’s one thing that the angels are, and certainly for the mystics who spring forth from that strain of mysticism that has come to be called theosophy. The angels, in this tradition, are real because the way things are is real. But angel-reality is a strange kind of reality. It is a reality that is embedded in life rather than being right there on the surface. And the communing with reality at this level always comes in flashes. And this kind of experience, the experience of suddenly understanding in a deeper and more profound way what has always already been the case, this is not the kind of experience human beings are going to stop having. So in that sense, though also perhaps in many others, the angels are among us, and the angels will always be among us and the angel talking is never going to stop because it is really just an aspect of us doing what we do. And maybe, when I think about it this way, I have to admit that perhaps I have spoken with angels, and that they have spoken with me.

Morgan Meis has a PhD in Philosophy and is a founding member of Flux Factory, an arts collective in New York. He has written for n+1, The Believer, Harper’s Magazine, The Virginia Quarterly Review and is a contributor at The New Yorker. He won the Whiting Award for non-fiction in 2013. Morgan is also an editor at 3 Quarks Daily, and a winner of a Creative Capital | Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grant. A book of Morgan’s selected essays can be found here. His books from Slant are The Drunken Silenus. and The Fate of The Animals He can be reached at morganmeis@gmail.com.