I’ve begun re-reading the work of David Jones, the Anglo-Welsh poet and artist and champion of the sacred and the crafted (what he called the extra-utile). Jones was a proponent of sacramental poetics, among the few really able to behold art as efficacious sign—the symbol that is also what it symbolizes, or a window upon that other world that art allows to show forth. And he was the untiring (but not polemical) opponent of all that is poised against that vision: the homogenizing, flattening, materialistic, utilitarian civilization of industrial modernity and the global consumerist civilization which is now more clearly than in Jones’s day bringing the Earth to the brink of ruin.

All that has to do with why I’m re-reading David Jones. It’s also fitting that I return to Jones after revisiting Mary Stewart’s Merlin Trilogy. I tried in my previous post to suggest how Stewart married the pagan and Christian sensibilities and life-worlds through a uniquely British sense of place, and by treating at least a portion of the story of Arthur and the Grail, which bears associations and parallels with the Christian Story. In many respects, Jones worked the same vein, though in verse mainly, and as a convert to Catholicism—or as he simply described himself in an essay (as usual eschewing the abstraction of isms) a Christian of “Nicene subscription.”

Although Jones was undeniably a genius, his art is rather opaque. The poetry reminds one of Ezra Pound’s. You can get into Chinese or Occitan by reading Pound; likewise you can (or must) pay attention to a fair bit of Latin and Welsh if you study David Jones’s poetry. You’ll also pick up the argot of the British soldiers of a century past. Like Tolkien (with whom Jones deserves to be compared at length), Jones fought in the trenches of the First World War. He was a soldier in the mightiest empire on Earth in the epoch when that empire shifted dramatically from its apogee to its phase of decline and fall.

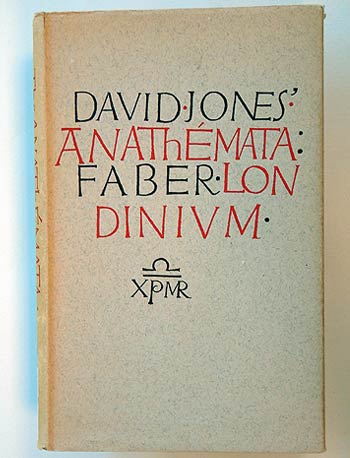

That experience as a soldier of worldwide imperium (as Jones would phrase it) contributed to his interest in the history of the Roman Empire and the Latin language that was the lingua franca of its military and administration. But Jones’s Catholicism also led him into Latin, and further into the history of the Roman Empire, for he was aware of the Christ-event as a historical event playing out in the Roman world. Jones’s imagination was captured by the Christian Story, particularly the Passion, and just as he understood the Mass as a reenactment of that story, so he sought to retell it in his poetry. In fact, Jones’s masterpiece among his published work, The Anathemata, is deeply structured by the Mass, and his uncompleted magnum opus, The Grail Mass—well, you can tell by the title alone where the artist’s attention was focused.

The grail of course has pre-Christian Celtic origins. Jones’s partial Welsh ancestry seems to have contributed the other half of his abiding artistic vision. In juxtaposition to his commitment to the Catholic (if not always so much the Roman) vision, Jones the artist was committed to his native place, indeed to what he called the tutelar of place. This is to say that he was a devoted member of a universalizing, transcendent religion, but at the same time a lover of the spirit of place, of all things earthy, immanent, particular. His interests were, if you like, cruciform: the horizontal line of this-worldly concern, and the vertical line of connection to the otherworldly. The point where the two lines coincide is the sacrament, and it is the unique enchanted place.

The place (so to speak) to begin with David Jones’s literary work is the short collection The Sleeping Lord and other Fragments, much of which was drawn from the unpublished Grail Mass. Jones had a sense that all his work was fragmentary, that no art is ever really complete in this life, on this Earth. Yet fragments nonetheless compose a whole. Put another way: it is the particularity of places, their limitation, that allows them to be woven into one fabric of difference—of language, of cultus (worship), of ecology and style—covering the world. And yet there are “fragments” precisely because this world is pierced by the transcendent in each place differently. How to justify the necessity of the fragmentary, or testify to its beauty? Here the poet describes the tutelar of place, in the poem (or fragment) of that title:

She that loves place, time, demarcation, hearth, kin, enclosure, site, differentiated cult, though she is but one mother of us all: one earth brings us all forth, one womb receives us all, yet to each she is other, named of some name other… / / she’s a rare one for locality.

…Though she inclines with attention from far fair-height outside all boundaries, beyond the known and kindly nomenclatures, where all names are one name…on known-site ritual frolics keep bucolic interval at eves and divisions when they mark the inflexions of the year and conjugate with trope and turn the season’s syntax, with beating feet, with wands and pentagons to spell out the Trisagion.

The tutelar or guardian deity is feminine: linked with the Mother of God in Jones’s mind and religion, and Mary linked with the pagan practices of the Classical and northern European worlds that interested him. What is striking to me in this passage, apart from the emphasis on locality, is Jones’s combination of the utterly immanent idea of the divine with the transcendent divine—that which is beyond nomenclature and boundary—which culminates in his invocation of the trisagion (“thrice holy”) portion of the Christian liturgy. For him there is no necessary conflict between local worship and the worship of the transcendent universalizing religion to which he adhered. In fact, the one must be approached through the other to be really understood and lived.

Without both of these cults, the universalizing and the local, humankind and in a way the Earth itself cannot much longer endure. Jones saw this, but he also saw how there is tension in this necessary coincidence of opposites, tension between culture and civilization. If the fragments coalesce immanently, in human empire, rather than transcendentally (and paradoxically) in the tutelar of place, the result is desolation. In one of the “fragments” of The Sleeping Lord, Jones has a Roman officer in Palestine a little after the Christ event (i.e. at the height of empire) state: “The cultural obsequies must already be sung before empire can masquerade a kind of life.”

Like many people today, David Jones felt he was living through a great historical turning. He felt his culture or civilization—call it whichever, it was built equally of pagan and Christian cultus—coming to an end. We have now perhaps lived beyond that ending without living beyond the truth and necessity of that mixed worship. We, like the poet, are looking for the Living God as we lurch toward the next phase. We strive to be open; we strive not to despair:

For it is easy to miss Him

at the turn of a civilization.

Jonathan Geltner lives in Ann Arbor MI with his wife and two sons. His translation of Paul Claudel’s Five Great Odes is available from Angelico Press and a novel, Absolute Music, is forthcoming from Slant. He writes more about the meeting of fantasy and fiction with theology, philosophy, music and the sense of place at betweentwomaps.com