Praise, pilgrimage, and poetry

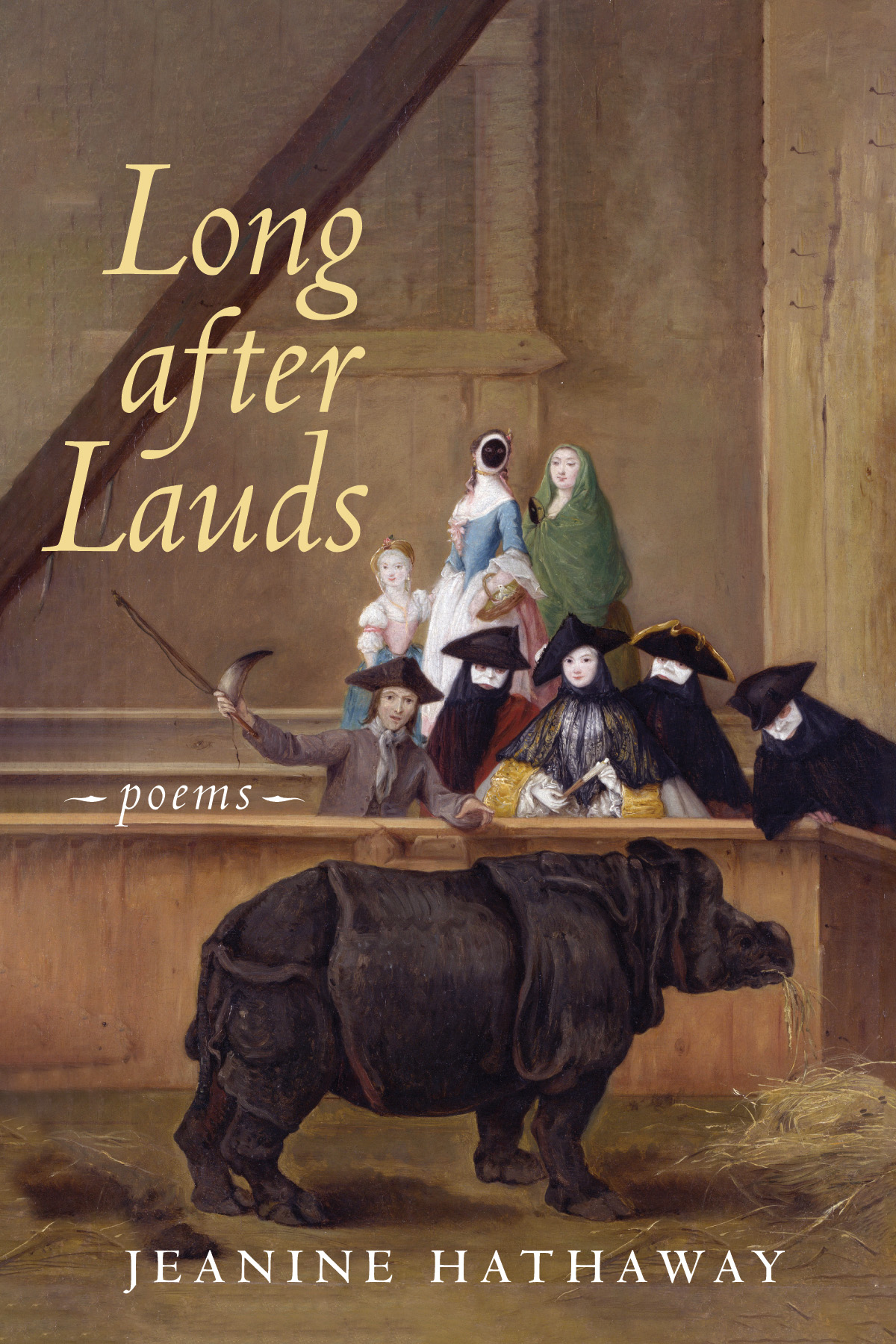

There could not be a more fitting title for Jeanine Hathaway’s new poetry collection than Long after Lauds. Lauds is a monastic morning prayer, and Hathaway was a Dominican nun for nine years starting in 1963. Lauds is also Latin for “praise,” and these poems probe what God and human life are like long after you can simply praise them.

With delightful wit and grace, Hathaway explores in these poems what it means to live a secular life after being grounded in Christian community. Take “Routing,” a poem that pictures a sister’s brain, preserved for research on Alzheimer’s disease, “in a plastic tub shipped on the UPS truck next to my / high-fashion catalog choice.” The poet then plays with the concept of choice: “I gave up a life of promise, simplicity, direction, and chose // or was chosen—I want it both ways—to choose me.” She has routed her life away from the convent.

Yet the convent remains strong in Hathaway’s consciousness. Woven through the book are poems about the “ex-nun,” a character she invents in order to hold both perspectives—the secular and the religious—simultaneously. Just by naming this character in a poem’s title, Hathaway helps us see everything in the poem differently; the “she” carries her convent past with her wherever the poem goes.

So, for instance, in “Mid-Life, the Ex-Nun’s Body Tells the Truth,” she is undergoing a diagnostic medical procedure. The radiologist “traced monastic points: // detailed masonry under scaffolding of ribs, past curtains / of lungs.” (That line-break is trademark Hathaway: we picture literal “curtains” until we drop into the next line’s “lungs.”) Then the radiologist continues “Around the courtyard, bronchial trees / the lime-white cloister walk.”

In “The Ex-Nun’s Death,” the shock of the title is immediately cushioned by the first line: “will not be as she’d imagined.” Yet, with amusing irony, the poem goes on to imagine the ex-nun’s death. With her long-ago first communion students at her bedside, she leans toward them “to hear each / whisper a family rage or wager . . .” (here we see Hathaway’s typically playful internal rhyming). And then comes a pun on the nun’s clothing: “Out of habit / they reach for her.”

The book’s closing poem, “Sabbatical: Morning and Comfort,” aptly concludes Hathaway’s vision of her religious past intertwined with her present. The speaker’s boarding house room is her “cell”; she awakens “in candlelight’s secular Matins.” In the poem’s final alliterated words, she hears her landlady’s “pages of newspaper / turn lightly, like leaves, like Lauds.” This, the only mention of Lauds in the book, is in a simile. Lauds itself has long left the speaker’s life; but something like Lauds remains.

Click here to read more in Christian Century

Peggy Rosenthal is codirector of Poetry Retreats and author of The Poets’ Jesus (Oxford University Press) and Praying the Gospels Through Poetry: Lent to Easter (St. Anthony Messenger Press).