We recently spoke with author Moira Linehan about her new Slant book, Toward

Toward is your third collection of poetry. Why don’t you begin by talking about how Toward follows your other two collections, If No Moon and Incarnate Grace, as well as how it moves beyond them.

Yes, there is a continuum in these collections. First and foremost, I see myself as a landscape poet. For close to forty years I lived in the same home that bordered a small pond northwest of Boston. Poems about that landscape itself or poems with that landscape as background are in all three of my books.

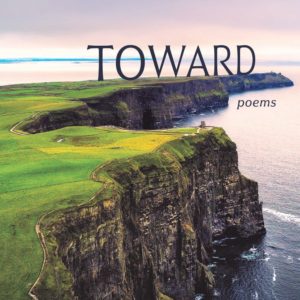

Ireland is the other significant landscape in my work. I have been lucky to return there a number of times. I identify with Andrew Wyeth whose paintings made two landscapes memorable: Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania and Cushing, Maine. He would talk about how “easy” it is to find new subjects in new places. As I understand it, the challenge he liked was staying in, or returning to, the same place and looking again, seeing what else, what more, was there. I, too, have tried to uncover “more” in the places I enter and re-enter.

This third collection continues a long line of grief. I mean, of course, a profound grief, the loss of a fundamentally significant person. Nothing ever comes close to replacing such a loss. While in early grief there is much anger, the grief poems in Toward come from later years. And later grief has some wisdom to it, if only the understanding that such absence never goes away.

What might be considered new is the craft work, especially the way I have deepened or strengthened the sonic and imagistic connections between subject and theme, theme and language. I want these poems to be read aloud. Sounds can support sense and tone and feeling. I have been working to exploit that characteristic, the power of it.

To stay with your landscape poems a bit longer: many of them have walking as background or subject. Will you comment on that?

I use “Toward,” the title poem of this collection, to draw attention to the speaker as walker and as someone who presents what she notices. But I also want her to be seen as someone who notices more deeply, looks more intensely at this world as she keeps walking. As the saying goes, If you want to see something new, walk where you walked yesterday. I most want the reader to see this speaker as grappling with what is so hard to put into words, what is beyond words.

Or as Paul Claudel says in the epigraph to my poem “Spirit Seeking,” grappling with the fact that That which each being lacks is infinite. How do you get that into words? Maybe I never will. But I keep trying. I keep moving toward that.

What’s interesting to me, for all your talk about walking and noticing, you also have poems about needing to leave a place. For instance, a poem like “The Sculptor and His Muse,” where you imply the muse will have to untangle herself from the artist if he’s ever going to make another statue. Or in “The Math of It,” where you end on “harbors I must leave.”

Yes, but that leaving, that untangling is always for the sake of seeking the beyond to which this world points in all its mysteries and beauty.

Some have commented on the crafted nature of your work. What do you think they mean?

As my friend, the poet Mary Pinard, always stresses, the root of the word poetry emphasizes making. Poems don’t “arrive” as whole cloth. They come from re-writing, from revision upon revision, from setting the work aside, sometimes as Elizabeth Bishop said about one of her poems, for fifteen years. So, I have never had a poem just drop into my lap or laptop. Each comes from work.

Another way to possibly explain this is to point to a couple of poems. Take, for instance, the first poem, “Where There’s a History of Famine.” That is set on cliffs in southwest Ireland, in a place of land’s end. So, I use the justified right margin to have each line bump up against a wall, a border, an edge to mirror the feel of that land and what its history might do to one’s soul. Or what it did to mine when I was there. I like it when the form of the poem fits the subject.

Or, to take another example, “Entering the Cill Rialaig Landscape.” I began that on the plane back home from there to Boston. I made five lists of words, each with a strong long sound of one of the five vowels. Then, back home, over time I used those lists to create five sections, each with its own long vowel sound, to try to capture the breadth of that place.

In “Echogram,” I have one strand echo or go back and forth with another: suggestions from an 1833 book about how to be a frugal housewife call to mind my husband, who taught economics. Again, I want the form to enact the way grief echoes in my life.

Tell us what you have been working on since you put this collection together.

I have been exploring the world in which my mother’s mother lived and worked. She is not someone I knew. And since my mother died just after I left high school, there is not a lot I know about that side of my family. I do know my grandmother was born in France and by the mid-1890s, was a dressmaker in Paris. There she met my grandfather, a tailor, whom she married. In 1905 they emigrated to Boston where they set up shop, Jules Wacha & Company. I decided to try to know more about my grandmother by studying the art she could have seen at that time, particularly paintings of women in fashionable dress. I am calling the manuscript & Company to remind the reader of how much I don’t know about my grandmother, in particular, and how much we all don’t know about so many women of that time, in general.

So, do you think you are done writing about Ireland?

By no means. I was in Ireland a year and a half ago. I planned to be there this past April. But then Covid arrived. I deliberately requested a voucher from Aer Lingus rather than cash because I wanted a symbol that says I will return. Andrew Wyeth would agree there is yet more there to move toward.