We recently spoke with author Claude Wilkinson on the occasion of the publication of his poetry collection, World Without End.

What is the significance of your collection’s title?

World Without End, the collection’s title, is derived from last words of the Gloria Patri, which suggests tended continuance, though the preceding words, “as it was in the beginning, is now and ever shall be,” are also echoed by the book’s overarching theme, which explores the seemingly infinite spiritual implications woven throughout our experiences of the natural world.

The collection includes meditations on family and community, spiritual worldviews, art and its many object lessons, and nature’s endless source of ever relevant metaphor. World Without End is meant to be mimetic, hence the poems not only correspond with other poems in their section but also with poems in each of the other sections of the book, and even with poems in my earlier collections, just as all creation is interconnected.

For example, the opening poem, “Among Other Things, My Father Teaches Me How to Mow Grass,” reveals a troubled patriarchal relationship, which is revisited in the poem “Salvia.” Both poems explore attempts at conciliation between father and son through yard work, or restoring order in the garden, so to speak. Oftentimes exultant, each poem in World without End is nevertheless haunted by its own broken Edenic bond.

Are the poems set in a particular place?

Much of the title poem is set in Wales, but the poem also references Canada and alludes to Mississippi. While some of the poems in the collection are geographically located, their lyric quality keeps them from being exclusively regional.

I’ve been asked whether I see myself as a Delta poet. Robert Penn Warren—one of my early influences—when asked if he considered himself a Southern poet, responded, “What else could I be?” James Dickey, another Southern poet whose work I admire, didn’t appear to shy from regionalist elements in his writing either. However, I view my tie to the South in general, and particularly to Mississippi, in a sense more akin to the much broader citizenry exercised in Derek Walcott’s poems. Of course, his work explores and expresses his West Indian heritage, but the poetry itself never seems bound to, or limited by, any circumstance of geography. While my poems are generally less cosmopolitan than Walcott’s, they are ultimately as universal.

Reading the Earth, my first collection, presents what may seem a Southern sensibility, which is true to a degree because of the use of such tropes as river baptism and hunting. But my poems have never been intrinsically linked to a particular region beyond their obvious enthrallment by the natural world. And while a strong sense of place felt in my poems is frequently cited, I believe readers are reacting to the clarity of setting which my language conveys rather than any uncommon bond that I have with the South.

What was your process in writing these poems?

My method of writing remains constant. I receive an idea through an experience, an image, or someone’s use of language. However, the actual writing of World Without End progressed much quicker than it did with my other books in the past, as most of the forty-five poems included were begun and completed within a span of the year following publication of my previous collection, Marvelous Light. Once I became focused on the paradox of a world continuously ending that is nevertheless perpetual, an organic, unifying theme bloomed with each successive poem. I don’t write poems with the goal of a book in mind, nor even publication of individual pieces. When a theme emerges from a significant group of poems, only then do I think in terms of honing them into a cohering work.

What is foremost in your mind when you set out to write a poem?

Foremost, I want my writing to be worthy of genuine poetry’s rich tradition, which to my mind entails the language being accessible, meaningful, uplifting in some way, and rhythmically beautiful. Trendiness, whether as the currently prevalent abstraction stemming from academia, the artless advancing of propaganda, or in any of its other guises, is anathema to my aesthetic. Howard Nemerov once asked in a poem, “If poetry did not exist, would you have had the wit to invent it?” Regrettably, without the capacity to do so, many now are trying to reinvent an already profound and beautiful art.

What shapes your aesthetic?

Regarding poetry, my aesthetic is shaped by an appreciation of beauty, not merely in the accepted sense of an ideal, but perhaps also in the way something uniquely functions, or even in its impenetrable purpose. Often the beauty I encounter is frustrating, as it’s presented in my poem “Weed,” or it can be sinister and simultaneously paradisal, as it seems in the poem “Cottonmouth.”

World Without End approaches notions of beauty through varied perspectives, such as my seeing a bluebird alighting in some nearby wildflowers being a harbinger of hope for my friend suffering from Parkinson’s disease, or even beauty’s possible manifestations through insanity, as in the poems “Walter Anderson Regrets Killing a Sea Turtle” and “Vincent’s Flowers,” about mentally anguished painters Walter Anderson and Vincent van Gogh. The poems of Warren, Walcott, Dylan Thomas, May Swenson, Mary Oliver, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Dickey, E. E. Cummings, and the like are those to which I return, and the standard to which I adhere.

To which of your previous poetry collections is World Without End most similar?

Perhaps ironically, poems in World Without End are most reminiscent of those in Reading the Earth, published some twenty years ago. There is again a focus—albeit an expanded one—on the connection between natural and spiritual realms. However, World Without End, possibly having lost the incandescence of a more optimistic, youthful viewpoint, instead offers the quasi-luster of a sage. The natural world and the idea of beauty are paramount in my poetry because they embody so much of what interests me about the universe and purpose. Again, there are many literal and symbolic references to birds, as there are in Reading the Earth and also in Marvelous Light. Snakes, in World Without End, are still implicit reminders of a fallen nature, and ekphrasis remains a useful method of summarizing our human condition, as in my other collections.

In that you are a painter, as well as a poet, do you sometimes notice correspondence between your visual art and literary art?

Certainly there are similar lyrical qualities shared by my paintings and poems. The quality most often mentioned by others is my use of color in both mediums. But while I use color to accomplish different aims in each art form—in painting to create mood and capture inspiration, and oftentimes in poetry for symbolic effect—there’s still a perceivable association.

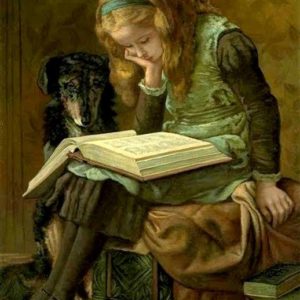

With my first book, I began a tradition of using one of my paintings as the art for my book jacket too. It wasn’t that I did illustrations expressly for my book covers, but for each publication I found at some point that I had made a painting that perfectly announced each book’s essence. For instance, Solitude, the painting used on World Without End’s cover, was done from photographs I took in Nantucket thirteen years prior to the book’s completion and publication, yet the image reflects the poems’ sentiment throughout.