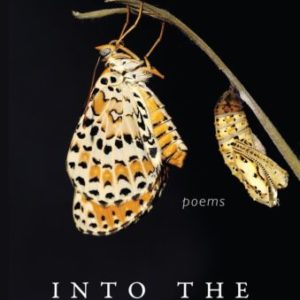

We recently spoke with poet Robert Schultz about his new Slant book, Into the New World.

The poem that opens your collection, “When the Magnitude of the Possible Dawned,” is a tour de force, its sections ranging from the comfort of family time in a backyard to the devastation of the Hiroshima bombing and back home to the hearthplace again. Is this poem something of an overture, a way of touching on all the themes that will follow?

Yes. I didn’t plan it, but when I assembled this manuscript I felt that “Magnitude” treated the book’s central concerns, placed them in relation to one another, and established a certain scope within which the following poems could do their work. Putting this book together, I’ve drawn from poems written over a number of years, and it feels as though, somehow, these poems together have found their moment. Family, home, and hearth known within the tragedy that is history has long been a theme of mine, but I could not have anticipated our extraordinary experience just now of withdrawing into our separate homes to combat a pandemic.

In that opening poem you say “We must be fire…we live by burning / Slowly.” Could you elaborate on that a bit?

The phrase leading into your quotation is, “To live within this involving flame…,” and I hope the earlier parts of the poem have made palpable the flames of history—war, disease, and “the thousand natural shocks the flesh is heir to”—which surround this young couple in their first years of parenthood. They have also witnessed with horror the misfortune of another couple whose child, “Aaron Bobb,” is dying of cancer. Within this fearsome context, even the night sky looks like a fiery cauldron “of creation and decreation.”

I wrote this poem in our first child’s first year, when the possibility of loss took on a new magnitude, and I began it on an anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing, after reading an account of the suffering on the ground. I worked on the poem for 18 months, seeking to write my way to an emotional safe haven. There is no safe haven, of course, not even in the green chapel of nature. All life, all metabolism, is a burning—in health a “slow” fire—and the best we can do, with courage and solidarity, is to burn together slowly.

You take on religious and spiritual experience but those realms don’t seem to offer any form of easy consolation. In one poem you say “Only unsettled / do we live in hope.” What’s that all about?

Right. In my view, religious and spiritual experience is a source of consolation, but not easy consolation. Complacencies and certainties are illusions that most often lead to hubris, judgment, and division. Think of the way political ambition was cloaked in religious dogma during the crusades, think of the contemporary Middle East, think of the entwinement of religious and political dividedness in our own country today.

When asked not long ago to deliver the Phi Beta Kappa address at my alma mater, I described “An Ethic of Uncertainty.” Friends have suggested that “uncertainty” is too negative, that I should talk about humility or openness, instead. But I wanted to name the disease in its antidote. Of course, we wish to be “settled,” safe in certain knowledge, but faith as the saints have described it involves struggle, trial, striving, and a continual seeking. All knowledge, spiritual or scientific, is continually in process. I love A. R. Ammons’ marvelous poem “The Misfit,” in which he celebrates: “the one observed fact / that tears us into questioning” and “leads us on.” “Only unsettled / do we live in hope” of further revelations. Of course, you are quoting from my poem “The Highest Emblem in this Cipher of a World,” which draws from Emerson’s “Circles” essay, which I think is a marvelous ode to the venturesome life of the mind and spirit.

Many of your poems focus on war. On the surface it would seem that the lyric is not a form that can comprehend the destructive force of war, but you seem to challenge that. Where did that impulse come from and what can poetry do to help us respond to the phenomenon of war? At the same time, many of your poems are set in a domestic, even pastoral world—of porches and fireplaces and backyards. Is it difficult to write of those things without idealizing them?

I’m glad you have asked me two questions here, because, to me, these subjects are related. I feel that my poems of home and nature must take their context within wider realities of history and war. The “fortunate man” of the opening poem, at home with wife and child, must reckon his place within a human frame that includes all manner of suffering. His good fortune—family, intimacy, love, beauty—must be known to shimmer in this context, vulnerable as a bubble in the wind.

I grew up during the Vietnam-American War, drew a high number in the draft lottery, and did not have to go. My birthdate, drawn from a spun drum, came up 261st, so how could I not count myself lucky and feel now, as a writer, a responsibility to set my context within the experience of others who fought instead of me, regardless of how I felt about that war. I think this is why I have found it necessary to try, however futile the attempt, to write war poems—to witness to the enormous human cost of war—though we finally must agree with Whitman that “The real war will never get in the books.” And because I have never been a combatant, I often have approached the subject of war through contemplation of its memorials, as in the poems “Gettysburg” and “Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Night.”

Your poems are written in many forms—varieties of free verse lines and shapes, as well as received forms, including rhymed quatrains, the sonnet, villanelle, ghazal, pantoum, sestina, triolet, and Dante’s terza rima. How did this happen? Do you begin with the idea of writing a sonnet, for instance, or does the poem’s matter suggest its manner?

The poems have happened in all kinds of ways. I was lucky that in college I worked with a mentor, the poet Gracia Grindal, for whom forms were important, so I tried them and got to know something about the way each moves, both musically and with its own shaped rhetoric or logic. I experienced how forms with repeating lines, like the villanelle and pantoum, can weave a spell or build a vehemence, and how the sonnet turns through its two parts, often enacting a drama of problem and solution. So, sometimes I have intuited that a poem will be short with a pivot in the middle, and the sonnet form has come to hand. (I have also found rhyming generative, often fetching a word I wouldn’t have found without the rhyme “emergency.”)

But sometimes I deliberately have chosen a form as a kind of allusion. I wrote “Drifting Souls,” which describes a photograph of soldiers stepping through long grass in Vietnam, in the terza rima of Dante’s Inferno. And for years before I wrote “Elegy” I wanted to use terza rima’s movement of rhyme sounds from inner to outer lines to express the circulation of water in a fountain. Most often, though, when I hear lines that want to make a poem they don’t arrive with implications for meter and form; the poem needs to find its own shape, and that’s harder.