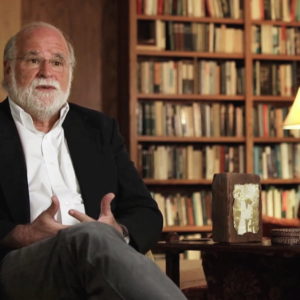

We recently spoke with author Daniel Taylor about his new Slant book, Woe to the Scribes and the Pharisees.

There have not been a lot of novels written about Bible translation, much less mysteries about Bible translators dying unexpectedly. Why did you choose this subject and setting for a novel?

In part because I worked on such a translation as a stylist for over ten years and found the process intriguing. I was very aware that we were dealing with ultimate things—and that such work entailed a great deal of what one might call cosmic responsibility. It was very much a human effort, involving personalities and ideologies and theologies, but also with the ever present sense of working with eternal things. Such a situation provides a natural ground for fiction, though fiction has rarely, if ever, explored this particular topic. The element of death simply presented itself. Such a topic and setting are of course rich with novelistic possibilities.

In this novel we find the central characters of the first two novels—Death Comes for the Deconstructionist and Do We Not Bleed? Jon Mote and his special-needs sister Judy are back again—and there’s a bigger role for Jon’s wife Zillah. What continues and what has changed for these characters since the last novel?

Judy, herself, is unchanging. It would not be realistic for her to change because she is, in a sense, an elemental force and the elements do not change. But she continues to be a catalyst for change, both in Jon and in another character new to this novel.

Zillah is more fully developed than previously, as is her relationship to Jon. He finds that many of the challenges of his life generally are mirrored in his relationship with Zee, and she, like Judy, offers him help on his way.

Jon continues his pilgrimage towards something like wholeness and Judy continues to be his resident saint. He continues to think too much and achieve too little, but he is making progress, though it is threatened by dark events. He has gotten back together with Zillah and is determined to make his marriage work and give his life in general a semblance of stability—with mixed results. God continues to haunt him, and he continues to run both away from and toward God at the same time. All this mixes in with his new role as a book editor that has made him part of this Bible translation project. He’s still looking for home and getting closer.

Where does the title come from and who does it refer to?

The phrase comes from Matthew 23 and is part of a dark warning to religious folks who parade their piety and learning but are in fact hypocrites and “blind guides.” This loosely parallels the scholars on the translation committee who are confident of their learning and their theologies/ideologies and yet display little in the way of God’s grace.

The scholars clash constantly, over issues large and small. These head buttings reveal both personality and theological types, offering opportunities for investigating both character and intellectual currents of our own time. And Jon, along with the reader, tries to make sense of both.

Can you describe something of what it was like to write this novel?

Well, it involved the use of both memory and imagination. Memory of more than ten years on a Bible translation committee as a stylist, which provided me first-hand knowledge of the kinds of issues that arise. And imagination because the members of the committee in the novel are not—and I cannot emphasize this strongly enough—in any way based on the members of the committee with whom I worked and whom I love and admire. I had to imagine the kinds of characters that might be chosen by a benighted New York publisher that knew nothing of the Bible and chose committee members solely on the basis of diversity and name recognition. Turns out they do not get on well at all.

This novel is a satire—a kind of intellectual-spiritual comedy—and the characters participate in the exaggeration that is a common feature of satire. It is also deadly serious, as comedy often is.

A challenge in this novel, as in the others, is to meet the expectations of genre—in this case a certain type of mystery—and at the same time explore character and themes that are not typical in that genre. I consider the ongoing Mystery in this mystery series to be similar to Milton’s in Paradise Lost: “to justify the ways of God to men.” Only I would substitute “explore” for “justify,” and I’ve limited it to one man, Jon Mote, who is both not me and not completely unlike me.

It is the Mystery of the human experience in a universe that may have been created by God. Is that topic big enough for you? It would be limitless hubris to think one was breaking any new ground on such a quest, but it’s where Jon Mote finds himself.

Can you say more about your background that is relevant to your writing of Woe to the Scribes and the Pharisees?

In the second novel in this series, Do We Not Bleed?, I drew on some years living in a group home with adults with intellectual disabilities, and this novel draws, as I said, on my experience on a Bible translation committee.

At the same time, I was a professor of literature for almost forty years and wrote various books, among others, having to do with seeking to live within a religious understanding of reality. This is not something that is written about enough in fiction in the last hundred years, especially not with sympathy and without bitterness.

Jon Mote is on a pilgrimage. He knows something of where he has been, but not enough of where he is going. That is the case with many these days, and readers may find Jon’s journey not unlike their own. And of course my work as a stylist on a Bible translation (responsible to make the English more effective) provided much of the nuts and bolts understanding of the Bible translation process. I acknowledge that things get more out of control in this novel than would be typical. This is definitively not how things go on most translation committees, but it’s how things went on this one.

Do you anticipate any more novels in this series or is this the end?

Jon is looking for home and he is not home yet. I think a fourth novel is required and will be the last. It is currently in process. I do not know if he will get there or not. That’s how it is with writing fiction—you follow your characters around and watch and listen and often do not know any more what will become of them than they do themselves. And readers, if willing, are along for the ride.