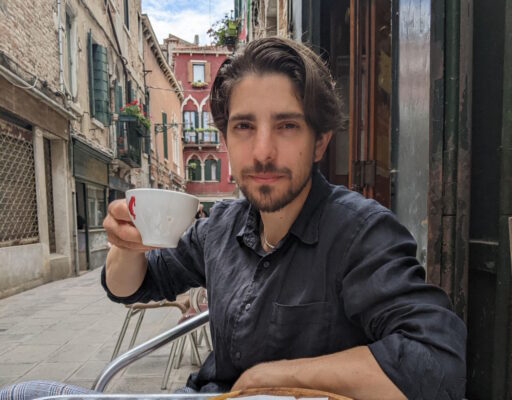

We recently interviewed Matthew Porto, author of Moon Grammar, a debut poetry collection just published by Slant.

This is your book publishing debut so tell us a bit about yourself.

I’m an Italian-American teacher and poet from Long Island, NY. I went to Boston University for an MFA in Creative Writing, concentrated in poetry, of course. I studied with Karl Kirchwey and Robert Pinsky there, both of whom were pretty amazing. After that I went to Texas Tech University, of all places, for a PhD in English, with the creative writing focus again. After the PhD I moved to Boston, where I work as an associate professor of English at Berklee College of Music. I love the students there—musicians are the best!

Hobbies, interests?

I love baseball — Go Dodgers! That’s a Brooklyn legacy thing. My grandparents, on my father’s side in particular, were raised in Brooklyn after coming over from Calabria in southern Italy. What else? I’m a creature of the city, so I enjoy getting out and exploring, seeing the variety of human life at every turn. Boston’s a very walkable city with rich history, of course, and a lot of architectural character. I chose it for those qualities. What I always say is that it’s as close as I can get to Europe here in the U.S. Also, I work as a tour guide in Boston. That has allowed me to immerse myself in its history, in the secrets the city both conceals and reveals.

You’ve mentioned your Italian heritage a couple times. Is that legacy important to you? And to Moon Grammar?

Very important. I may be a lapsed Catholic, but, like it or not—and usually I am at peace with it, even proud—Roman Catholicism is at the heart of my cultural heritage. I attended Catholic school all the way through college—counting the University of Scranton, a Jesuit institution. All the angel stuff in Moon Grammar has its origin, I think, in Catholicism and its art: stained glass, gilded sculpture, icons, and so on. It explains the interest in biblical myth as well—after all, those stories were present to me in readings and homilies from Sunday mass, which I attended every Sunday until I went off to college, and sometimes after that too. For me, I see all of it as great literature now.

So when did you get started on Moon Grammar?

The book has its roots in my doctoral dissertation, which had a creative and critical component. Strangely enough, the vast majority of the poems in the collection never found their way into a workshop during my studies. The poems I brought to workshops have largely fallen out of my body of work. It was all practice until the Moon Grammar poems came in a bit of a flood after my doctoral coursework was done and I entered the qualifying exams and dissertation stages. The workshop experiences certainly made me a more attentive writer and reader though, of course.

The title of the book is striking. How did you come up with it?

Well, like many things in the arts, it’s borrowed, or should I say stolen? The phrase “moon grammar” comes from Thomas Mann’s biblical tetralogy, Joseph and His Brothers. Mann retells the story of Joseph, son of Jacob from Genesis, in four dense, massively rich novels. In the first novel, Stories of Jacob, Mann employs the term to describe an ancient people’s way of seeing individual identity as shifty, blurry, and subject to direct influence from the ever-present ancestors, who prefigure our actions. In other words, Jacob might speak of his father Isaac as the one who was nearly sacrificed by Abraham, and of himself as the one who deceived Isaac by wearing lamb skin, but within the grammar of the moon these things may not be literally, empirically true. In the ancient mythic worldview, it mattered less, according to Mann, whether one person literally, provably had such and such experience. In other words, the stories live in the descendants of the tribe, as archetypes that manifest again and again.

That’s fascinating, and a bit esoteric. How did you manage to apply it to poetry in the twenty-first century? To a modern self?

Well, like so many of us, I was looking for a connection to the past, and I wanted to believe it was possible despite the dizzying changes of recent decades. Mann’s idea was attractive because at its heart it’s actually quite simple: it’s that we can believe unironically in the radical presence of the past, of mythic predecessors, of a true link between us all, and language can express that belief unapologetically.

In the second section of the book, the focus shifts to a modern speaker. The angel fades until it reappears in the last section. In those middle poems, the focus is on travel, and relationships, and landscape, but myth is still present too. The modern speaker finds himself confronted with shattered tradition and does what he can to reconstitute it. He looks for traces.

Fascinating. What about that angel figure? How does it fit in?

The angel was a shorthand for me. It stands for experiences beyond my comprehension—those life-affirming moments that really keep us going: a great conversation in which you seem to be truly in one another’s heads; a certain cast of light on tall trees; the moment when music and landscape become one. Our lives contain these moments, but how to talk or write about them? The angel was my answer to that.

Let’s shift focus a bit. How about your process? What gets you writing, starts the wheels turning?

That’s an easy one for me—reading! The initial impulse for me comes almost exclusively from other writers. I’ll be reading something with a clear mind, which is difficult to do these days, and I’ll be struck by a phrase, an idea, an image, and then I’ll start a draft. That’s how it happens for me. My inner life finds its way into the poems through the medium of other texts, so that I can really call my poetry intertextual. I’m always in conversation with other writers. That explains the presence of allusion in my work. Sometimes I feel like I’m on the hunt for epigraphs—the keynote to set off and define a new draft.

So which writers do you converse with in Moon Grammar?

Many. I’ve already mentioned Mann. As far as the concepts underpinning the book, he’d cast the largest shadow, I think. The Hebrew Testament and the Greeks in general are there.

As far as technical and stylistic models, I think the influence of the late Louise Glück should be obvious—I was reading her whole body of work while writing Moon Grammar. Her spare, declarative free verse had a huge influence on the sound and voice of my poems. For me, she is an authoritative, unapologetic voice. Derek Walcott is there too—I love the fecundity of his verse. He allows the images to grow as if naturally, as if they were an organism with their own instinct. And then the Modernists are everywhere for me—the use of mask, the recycling of myth, the melancholy tone as speakers face fragmentation and disillusion. I am thinking of Eliot and Pound and H.D. in particular.

What are you reading right now?

The Serpent Coiled in Naples by Marius Kociejowski, the early modernist novel Confessions of Zeno by Italo Svevo, and Ishion Hutchinson’s poetry. And then I’m always revisiting James Baldwin and a variety of poets for my literature classes.

Finally, are you working on anything else?

Yes. Inspired by the I think unjustly forgotten Swiss writer Gerhard Meier, I’ve been developing a series of interconnected short novels, or novellas—I’m not sure yet. And I have another poetry collection in the works that more directly engages that Italian ancestry we spoke about.