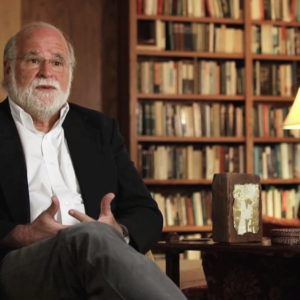

We recently spoke with author Daniel Taylor about his new Slant book, The Mystery of Iniquity

This is the fourth and final Jon Mote Mystery. Since murder mysteries are all to some extent investigations of evil, what led you to take on that mystery head-on in this one?

Actually, I believe most murder mysteries are about factual details (“whodunit” and how?), not about evil per se. Evil is assumed, not genuinely explored. Jon’s persistent questions throughout the series are “Why am I broken?” “What can I do about it?” and “Who can help me?” These are a subset of everyday questions arising from the ancient mystery we call “the problem of evil.” I, personally, and I think these four novels, are more interested in Mystery than in mystery.

One trigger for this particular novel was coming across the King James Bible phrase “the mystery of iniquity” (2 Thess 2:7-9). I found it a very intriguing phrase, one always relevant but no more so than today. (Modern translations lean toward rendering this “the spirit of lawlessness,” which certainly seems loose in the world today in many ways both overt and subtle.) What is evil? Why do we participate in it? What can we do about it? What or who can help us? In short, Jon Mote’s questions.

A theme that runs throughout the series and culminates in this last novel is that evil—or brokenness (ruptures in shalom)—can only be overcome (healed) by a force that is greater than the source of the evil itself. Contrary to much contemporary thought, evil is real, it is powerful, and it is beyond our ability to cure in our own strength. We cannot heal ourselves—neither with individual effort nor with social engineering.

While very interested in the mystery of iniquity, I am even more interested in the mystery of grace. Is there really such a thing—fundamentally—in the universe? If so, what is its nature, where do we find it, how can we embrace it? The primary conduit for grace throughout the series is Jon’s damaged sister Judy (with a boost from Sister Brigit), but Judy is only a conduit. Jon has to find grace’s source.

A central theme in the book is the immigrant experience and the ways that distant events can have repercussions in supposedly quiet suburban American streets. What drew you to that focus?

In my professor days, I taught a course entitled “Literature of the Oppressed.” We began with the Holocaust because it is a quintessential expression of what I and the students think of as oppression. But throughout the semester, I moved the readings closer and closer to home, exploring in the last half of the course expressions of oppression in America and raising the uncomfortable question of how we might ourselves be participating in it. Something like that progression occurs in the novel.

The opening scene takes place in a torture chamber in the Middle East. The next scene is one of bland domesticity in Jon’s suburban home, now peopled with Jon, Zillah, and their triplet children. The plot of the novel revolves around the meeting of these two worlds.

Americans are learning—almost for the first time—that great evil does not stay in its place. It doesn’t just happen “over there,” where we can occasionally go and “fix” things (see our modern history of foreign wars). Evil, we have found, comes here to us (think 9/11), and worse yet for our self-image, evil often originates here—with us as its agents—in our shared life as well as in our relations with other nations. This puzzles us. Aren’t we the “good guys”? Aren’t we the people with the right answers and the power to enforce them?—versions of Jon’s questions about his own life.

In addition, the immigrant experience asks us how we are to respond to those seemingly not like us. What do “kindness” and “compassion” and “justice” and “mercy” mean and how can we—including those who go to church—make them real in our lives and in our communities? These are recurring questions for Jon, a man trying to escape his long history of an obsessively inward gaze.

In this volume, Jon is back in church. Talk about that.

Religion is rarely explored in contemporary fiction, and church, even as a mere social institution, is almost non-existent, even though it is still a major factor in the lives of many millions of Americans. I consider that a failure to explore a key part of the human experience. And so I have consciously purposed to have at least one church service in each novel in the series, and there are even more than usual in this last novel.

Jon spent his youth and early adulthood running from his childhood religion, for understandable reasons that the novels explore. To oversimplify, Judy represents the possibility in his life that he is mistaken in equating his church experience with a God experience.

That Jon finds himself back in a church most evry Sunday, rather than just visiting as previously, is a mystery to him, but I think less so to the reader of the previous novels. He has been heading this way for a long time because there’s something in his bones—and in his sister—that is stronger than bad experiences and superficial unbelief can withstand. Luckily—read providentially?—this church is led by a pastor with wounds similar to Jon’s.

Jon Mote has come a long way—emotionally, psychologically, and philosophically—over the course of the four books. Did he ever surprise you along the way?

Unlike some characters, Jon doesn’t much surprise me because I’ve met him so often in my life—in others and in myself—that he seems more an Everyman than an unbalanced oddball. Much of my nonfiction writing has explored the borderlands between faith and doubt (or unbelief) and I have had exchanges over the years with a multitude of highly introspective folk wrestling, like Jon, with transcendence and angst. I am not Jon Mote (nor is my marriage that of Jon and Zillah, though friends sometimes imply as much), but I know how he thinks and feels and attempts, with mixed success, to act. If anything surprises me about him, it is that he seems to be making progress toward something closer to wholeness.

You’ve said that this is the final volume in the series. Will it be hard to let these characters go?

I don’t think of ending the series as letting go either of them or the issues the novels address. In part this is because so many of the characters are based on folks from my own life and so many of the issues are ones that I will always chew on—the possibilities of true transcendence and God and grace, the ground for meaning and significance in a life, and so on.

My wife, Jayne, and I ran a group home in the 1970’s for mentally disabled adults. As Jon discovers, I thought I was helping take care of them when in fact they were teaching me—about acceptance, perseverance, kindness, and finding simple joy in life. The similar characters in the novel are, quite literally, these same people. Judy was Judy, Bonita was Bonita, and eyes-in-the-sky Billy was Billy. All dead now, but not gone from my mind and heart and therefore not “let go.”

I’ve also left myself a return path. There are gaps in the chronology as the years pass from Death Comes for the Deconstructionist to The Mystery of Iniquity. I did this quite consciously to allow myself to come back and wedge a novel in one or more of those gaps. I have also toyed with writing a stand alone novel about the early life of Judy and Jon together as children and young adults. So I may be back with these folks again.