I happened to be in New York City a few weeks ago. It was during the weekend of the eclipse. It was the day of the eclipse, actually, that I ended up at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It was many years since I’d been in the museum. I’d taken a bus from my sister’s apartment in Harlem and gotten off a few stops early and walked down through the edge of Central Park. The park was starting to fill up with eclipse watchers. There was a tension in the air. Hard to describe precisely. People were going about their daily affairs. And yet, there was a sense of anticipation mixed with, I don’t know, not fear exactly.

Also, there had been an earthquake in the city a couple days earlier. The city rumbled for some seconds with a power that was coming from the low and deep places. You could feel that. The earthquake heightened the anticipation for the eclipse. But still a muted sense of anticipation. Perhaps it was the mood of people who aren’t sure exactly what they are waiting for and don’t want to seem too much like they care because they are not even completely sure that they care. A woman was sitting on a bench. Her hair was in a tight bun and she was wearing an expensive sweater. Her children were playing on some rocks. She watched her children, but she kept glancing up at the sky every few seconds. Her face was a mix of wanting something and not wanting to look like one wants something and not being sure what one wants anyway. That mood is always, to some degree, floating on the wind of New York City. I found out that it floats even heavier when an eclipse is nigh.

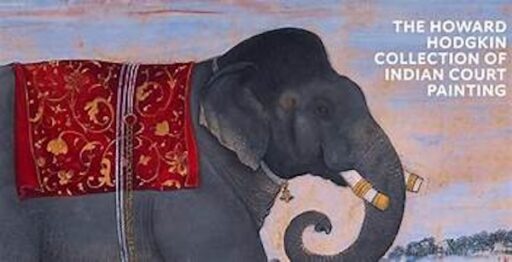

I was meeting my mother at the museum. My mother is both a great lover of art and completely unpretentious about it. Often, she simply stands in front of objects of art and smiles. We found ourselves in an exhibit entitled Indian Skies: The Howard Hodgkin Collection of Indian Court Painting. We were both suddenly astonished. I don’t know why exactly. I do know why un-exactly. The paintings are extraordinary. But what does that mean? I don’t know. I don’t know anything about Indian Court paintings. I’ve seen a few here and there, including some in India. But I don’t know how to look at them. I don’t know the history or the context or the way that these paintings fit into a narrative. I don’t know the codes. So I just looked, without context, without codes.

I was taken with the sense of space in those pictures. And color. Flattened colors for the most part: many ochres and yellows and light greens in the background. The color had the effect of also flattening out the space in which the painted scenes floated. There were quite a few pictures of elephants. Elephants in groups or alone, engaged in royal hunts or festooned for some kind of ceremonial purpose. Elephants in scenes that may have been mythological and elephants in scenes that may have been historical. All of them floating in a space with that muted but still somehow intensely powerful color in the background. The spatial arrangement of the scenes always somehow deeply disorienting. In one picture, an elephant seemed to be walking directly up the light blue background as if ascending into the sky. Clustered around the edge of the picture were all manner of other elephants and people banging drums, brandishing ornate spears, and blowing on wind instruments. All of this wonderful activity stuffed impossibly along the edges of the painting as the giant central elephant made his trek across and possibly beyond color itself.

In a daze, now, from the power and impact of those Indian Court paintings, my mother and I wandered out into Central Park. That’s when the eclipse started to happen. I only partially cared. I was thinking about elephants and the specific tonality of mustard yellow. The park was filled with people. I looked to the south and noticed again the new buildings that have been constructed along the southern edge of Central Park. They are so narrow. They don’t look real. Tiny tremulous shoots of steel and glass that seem to have shot out febrile from the landscape of buildings below them perhaps of their own accord.

Rarely had I seen so many people in Central Park. But there was less sound than I would have expected. There was a pervading silence that comes from those who wait. I wanted at that moment for the eclipse to be the most wonderful event in the history of the universe. I glanced up quickly at the sky. Nothing. We walked through the crowds. People were laying in the grass or sitting on benches or gathered together in pockets. But what, exactly, were we supposed to do? Just look? And when do you look, exactly, and for how long? I mentioned to my mother that we don’t know what to do anymore when a celestial event happens. In the ancient days, we would have danced and sung. Yes, she said, you are right. We should dance and sing. For a moment, she started to move around a bit and to sing something.

Then she pulled a pair of the protective glasses from her coat pocket. She handed them to me. I looked into the sky and the moon had almost completely passed in front of the sun. It was a pure blackness. And behind that, a pure radiance. But just a sliver. I took the glasses off again. The light in the city was muted and strange. The colors had become more pastel, like the backgrounds of those Indian Court paintings. I waited for an elephant to walk down from the sky. No elephant came. I took my mother’s arm and we walked through the crowds, through the park, through the mysterious, muted, effervescent light.

Morgan Meis has a PhD in Philosophy and is a founding member of Flux Factory, an arts collective in New York. He has written for n+1, The Believer, Harper’s Magazine, The Virginia Quarterly Review and is a contributor at The New Yorker. He won the Whiting Award for non-fiction in 2013. Morgan is also an editor at 3 Quarks Daily, and a winner of a Creative Capital | Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grant. A book of Morgan’s selected essays can be found here. His books from Slant are The Drunken Silenus. and The Fate of The Animals He can be reached at morganmeis@gmail.com.