Rabbi Jerry

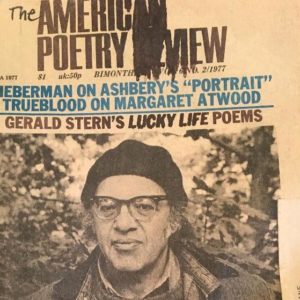

I remember the American Poetry Review, March, 1977, page 26, cows and bald hills of Tennessee and rabbis of Brooklyn, their foreheads “wrinkled” as their “gigantic lips moved / through the five books of ecstasy, grief, and anger.” That’s from “Psalms,” one of twelve poems by Gerald Stern, whose photo on the cover showed his own gigantic, Jewish lips.